- Home

- Melissa Hart

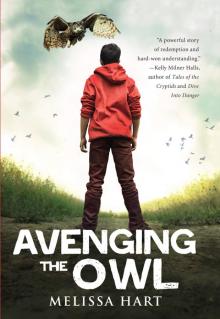

Avenging the Owl

Avenging the Owl Read online

Copyright © 2016 by Melissa Hart

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are from the author’s imagination or used factiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Sky Pony Press books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Sky Pony® is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyponypress.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-63450-147-7

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63450-610-6

Cover design by Sarah Brody

Cover image credit Stephen Mulcahey / Arcangel

Printed in the United States of America

For Maia, who loves the Earth

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE Raptor Means To Seize

CHAPTER TWO Owls = Death

CHAPTER THREE Say Good-bye to Hollywood

CHAPTER FOUR The Strongest Stories Are Born of Pain

CHAPTER FIVE Menace to Society

CHAPTER SIX Sergeant Bird Nerd

CHAPTER SEVEN Freedom of Mobility

CHAPTER EIGHT What Next?

CHAPTER NINE Eat Dessert First

CHAPTER TEN Alone

CHAPTER ELEVEN Not a Retard

CHAPTER TWELVE Nictitating Membranes

CHAPTER THIRTEEN Just Let Go

CHAPTER FOURTEEN No Longer a Butte

CHAPTER FIFTEEN Parents = Chaos

CHAPTER SIXTEEN Owls Call Out the Names of People Who Are About to Die

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN Solo’s Kriyā

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN That Owl Must be Destroyed

CHAPTER NINETEEN Home

Acknowledgments

Resources for Raptor Lovers

Resources about Down syndrome

About the Author

CHAPTER ONE

RAPTOR MEANS TO SEIZE

According to Mr. Davies’s junior high screenwriting class, the word means payback. But avenge is more than plain old revenge. Avenge is a word that yanks you to your feet—heart pounding and palms prickling with sweat—to root for the hero. It’s a word about justice.

In that old B movie, Them!, Sergeant Ben Peterson avenges the death of a little girl’s family by destroying the nest of giant mutating ants that slaughtered them. A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away, Han Solo avenged the destruction of an innocent planet by helping Luke Skywalker blow up the Death Star.

Sergeant Ben got away without being killed by mammoth ants. Han got a gold medal from a beautiful princess with really weird hair. But when I avenged the murder of the only thing that mattered to me, I got eight weeks cleaning poop off birdcages.

My new social worker told me I’d have to show up at the raptor place at the base of the mountain every single morning, no matter what. Forced labor, like those guys in the orange suits they let out of jail to pick up bottles and bags along the freeway. Only I’d be working with birds instead of trash.

I almost told my social worker no way. Throw me in the hole; give me a month in solitary over caring for a bunch of hawks. But then I remembered how my father had hung his head in the courtroom when the judge proclaimed his straight-A son a full-fledged At-Risk Youth. Dad went all pale and sick, looking ready to crawl back into his striped pajamas for another six weeks.

If he hadn’t already ruined my life, he would’ve broken my heart right then.

•

“Well … guess I’m off.” I stalked into the kitchen on my first day of community service and felt the trailer sway beneath my feet. I scowled at the orange flowered linoleum and glanced over at Dad. Maybe he’d take pity on me, give me a reprieve when he saw me in my oldest, rattiest clothes like a version of Oliver Twist.

“Be careful.” Dad hunched over the newspaper at the kitchen table without looking up.

I grabbed a banana from the fruit bowl and bailed, slamming the trailer’s joke of a screen door behind me. “You be careful, too,” I muttered.

That first morning, Mom gave me a ride to the Raptor Rescue Center. It took about a year for her purple Volkswagen bus to chug up the mountain road past the endless evergreen trees. Right as the bus almost blew a gasket rounding a curve, I named it The Big Grape. A lot rides on a name, and this one fit perfectly.

“This rig sucks.” I folded my arms tight across my ancient Rip Curl T-shirt and glared out the window. My pencil jabbed my butt through my shorts. I yanked it out of my back pocket and stuck it behind my ear. Mr. Davies always had a pencil behind his ear and a notebook in his pocket, in case inspiration struck and he had to scribble down a screenplay on the fly.

Did he miss me yet?

“You’ve got what it takes to be a writer, Solo,” he said on the last day of seventh grade. We stood outside after the graduation ceremony with the mist creeping up from the ocean, both of us in suits and ties. He put a hand on my shoulder. “Promise me you’ll keep working on those screenplays. Make your dreams come true.”

Dreams. I snorted, perched on the hard front seat of the ridiculous Volkswagen bus with exhaust in my nostrils. My life had become one big nightmare.

Mom shoved the accelerator to the floor. The Big Grape groaned in pain, bucking past a mailbox and straight up a super-steep hill. We pulled into a parking area beside some pavilion with a bunch of benches and lurched to a stop inches away from a tree.

“We’re here!” Mom’s smile worked overtime.

“Wonderful.” I stared out the window at a couple of blue-walled porta potties under more trees.

“What’s happened to you?” Mom’s smile vanished, and she morphed into Disapproving Maternal Character. “You used to be such a little gentleman. I don’t even know you anymore.”

I shot her the sideways evil eye. “I don’t know you, either.”

My mother wore ugly, chunky sandals under a long, swirly, blue and white skirt. She’d yard-saled her board shorts and her bikini; I wondered if she’d sold her diamond earrings, too. She looked like a hippie from the 1960s, all dressed up to sing and dance in Golden Gate Park … except for the warning look that flashed in her eyes. “Don’t be snarky, Solo.”

“Sorry.” I picked at the ancient stuffing spilling out of a rip in my seat. “But why’d we have to sell the Corvette? This bus is humiliating.”

Mom closed her eyes. “That Corvette was nothing but a status symbol.”

“You sound like Dad.” I unclipped my seatbelt, the better to turn around fully and glare at her. “What the heck’s a status symbol?”

“It’s something you own so other people will think you’ve …” She twirled a strand of sandy hair around her finger, searching for the right words. “Made it.”

“We had made it, Mom. That Corvette was a sweet ride.”

“You know perfectly well why I couldn’t drive that car after your father …”

Mom’s voice died, and she stared hard at something over my shoulder. I glanced behind me. A tall woman with a head of wild red hair loped toward us in jeans and green high-top sneakers. A bird the size of a Coke bottle perched on her gloved hand, ruffling his feathers in

a blur of blue-gray-brown-black-rust-white.

My mother recovered her voice and her smile. “I think that’s your boss.”

“Jailer’s more like it. She’s a prison warden.”

Mom’s jaw tightened. “Get out and introduce yourself. Don’t embarrass me.”

I rolled my eyes and heaved myself out of The Big Grape with my backpack held in front of me in case the bird decided to attack.

The woman stretched out her hand. “I’m Minerva,” she said, low and gravelly. “This,” she nodded at the bird on her wrist, “is Cyclops.”

Minerva’s voice gripped me, as relentless as her handshake, and forced me to acknowledge her sidekick. The bird flapped its wings, but stayed put on her arm. I squinted. Thin straps around his feet went to a hook that clipped to her glove.

“Cyclops is a kestrel—North America’s smallest falcon.” Minerva nodded at the bird’s right eye, scrunched tight in a permanent wink. “He’s partially blind.”

I’d never seen a bird this close up, not even a seagull on the beach back home. Its tiny beak curved like a fishhook and eight little sharp talons dug into the leather glove.

“It’s good to meet you.” My mother got out of the bus and clasped Minerva’s hand.

The kestrel flapped again. He peered at me out of his good eye and chirped. “Thank you for agreeing to help Solo,” Mom continued. “He really is a good—”

“The way I understand it,” Minerva’s voice interrupted smoothly, “Solo is helping us. Follow me.”

She strode up the driveway toward a lawn surrounded by trees with trunks thick as Monster Truck tires. Shadowy creatures lurked inside tall screened cages all around me. Suddenly, a creature somewhere above let out an ear-piercing shriek.

Ki ki ki ki kee!

I ducked and covered my head.

Caw! Caw!

“What the … ?” I leaped back, shaking in my sports sandals, and took shelter under a tree hung with bird feeders.

“It gets pretty loud around here.” Minerva’s voice remained calm, like we weren’t standing smack in the middle of Alfred Hitchcock’s horror movie The Birds. “We rehabilitate sick and injured raptors, but some don’t recover well enough to be released into the wild. When that happens, we can often find homes for them. Some of them end up staying here.”

My mother nodded and pressed her palms together against her chest, bowing slightly in some show of hippie-gratitude for Minerva’s mission. I rolled my eyes.

“That’s fascinating,” Mom breathed. “This is a silly question, I know, but what exactly is a raptor?”

She reached out an arm to pull me into the conversation. I moved away from her, still searching for a safe spot to get away from the birds.

Minerva nodded at Cyclops, who gripped her wrist even tighter with his evil little talons. “The word raptor means to seize.”

My hand flew to the bandage on my left wrist, testing for pain. I could roll down the hill below us and vanish into the trees. They’d never find me. I’d hitchhike back to California and …

“You might want to listen to this, Solo. It’s important information to know if you’re going to volunteer here. Visitors might come up to you with questions.” Minerva raised one eyebrow. “Raptors hunt with their talons, grabbing their prey with them. Then they use their beak to rip their prey apart. Let me put Cyclops in his enclosure and I’ll show you our peregrine falcon. Their hunting technique is fascinating.”

Minerva led Mom toward a cage. I stood rigid on the lawn. I already knew all about the way raptors hunt—had seen it up close and personal. The sun boiled the top of my head. All around me, sparrow-looking things twittered in the trees, flaunting their freedom high above the caged raptors. I thought about my friends out surfing back home and punted a small rock. It crashed down the hill and the bird near me screamed and flew back and forth, hitting the sides of its cage.

My mother’s voice drifted toward me. I caught the words shotgun and disabled boy before I slunk away in disgust to a spot where she couldn’t see me.

“Oh, well,” a voice beside me croaked. “Ha ha ha ha!”

I peered into a flower garden. Yellow butterflies floated into the trees. A squirrel curled its gray tail like a windsurfer’s sail, bawling out some blue bird on a feeder.

“Well?” the voice said again. “Ha ha ha ha!”

I spun around and stared into the nearest cage. A crow as black as my hair sat on a perch.

“Did you … did you laugh?” I stammered, real quiet. Too many loony tunes in my family already. No one needed to know I was talking to birds.

The crow cocked its head and looked at me sideways out of one shiny black eye. “Well?”

“You talk?”

Minerva crunched down the gravel path and pointed at a laminated sign near the cage, packed with information and a picture of the bird. “This is Edgar Allen Crow,” she said.

Mom whooped like it was the funniest joke she’d ever heard. “That’s wonderful! Just like the poet. You know, sweetie, Edgar Allen Poe.” She turned to Minerva. “Solo’s father reads Poe’s poem The Raven out loud to us every Halloween.”

Minerva pointed with a bandaged index finger. “The raven’s in the next mew. Her name is Hephaestus.”

An even bigger black bird with a long, curved beak flipped its head backward and looked at me upside down. “What’re you doing?” it demanded.

Mom clapped her hands. “This one speaks, too! Do all raptors talk?”

Her voice was giving me a headache. Beside me, Minerva massaged her temples with her fingers. Did she have a headache, too? Lately, it seemed like Mom never stopped talking and always in a high-pitched, frantic voice that made me want to walk around with wax plugs permanently stuck into my ears.

Mom and I used to be friends, surfing buddies, both of us heading out at 6:00 a.m. with our boards. But then, she’d turned enemy.

“Edgar and Hephaestus aren’t raptors.” Minerva plucked a long black feather from the ground and stuck it in the back pocket of her dirty jeans. “They’re corvids I rescued years ago.”

Mom peered into a food dish in the raven’s cage. “Is that tofu?”

“Yup. In the wild, they’d eat small birds and rodents. Here, they get cat food, fruit, and chunks of tofu.”

“Hear that, Solo?” Mom elbowed my side. I ducked my head, blocking her from my vision. Tofu was another one of my mother’s new instruments of torture. I hated the white spongy squares she cooked with rice or tried to hide in vegetarian chili. “Bean curd,” she regularly sang out in the trailer’s cramped, dark kitchen. “Nutritious and delicious!”

I tried to choke the stuff down at dinner. As I spit it out into my napkin, all I could think of was that nursery rhyme:

Little Miss Muffet

Sat on a tuffet,

Eating her curds and whey;

Along came a spider,

Who sat down beside her,

And frightened Miss Muffet away.

I swear, I’d eat a spider any day over some bean curd that—from the looks of Hephaestus’s food dish—even a raven wouldn’t eat.

“Solo, I’d like to introduce you to the other birds,” Minerva continued.

I looked up to find my mother walking back to the bus. Minerva tapped her sneaker impatiently against the gravel, a crease between her eyebrows.

“Well?” Edgar said.

I backed away. That crow gave me the creeps. “They’re all in cages, right?”

“The proper term for a bird enclosure is a mew.”

“Great.” The sun gripped the back of my neck. I shoved my sunglasses down on my nose and shuffled behind her.

“This is a northern harrier.” She pointed to a bird with a long tail. “They make their nests on the ground. Hers got destroyed by a haying machine, and she lost part of her wing.”

The harrier bent to pick at something dead on the ground—something with gray fur. My stomach lurched. I ground my teeth together, praying I wouldn’t throw

up.

Minerva moved to another mew. A blue tarp stretched across the bottom half, three feet tall. “That’s Artemis.” She braced her hands on her hips. “Never, ever go into her mew. She’s sitting on eggs, and it makes her moody. Let’s move on so we don’t disturb her.”

A grouchy bird. I bent and peeked through a rip in the tarp—nothing but gravel and a brown and white feather.

Minerva consulted her silver wristwatch with an owl on its face. She pushed her hair behind her ears, revealing silver owl earrings that glimmered. In a screenplay, Mr. Davies would have described her as a Hard-Core Bird Nerd … I just knew it. “I’ve got a preschool class coming for a tour at eleven,” she said. “I’ll tell you Artemis’s story later.”

I shrugged, then stopped dead in front of a giant mew that loomed twenty feet high. There sat two of the biggest birds I’d ever seen—tall as kindergartners, white heads gleaming above dark bodies.

“Those are the bald eagles,” said Minerva. They sat up on long perches, straight and dignified, twin presidents behind wire.

“They’re huge!”

At the sound of my voice, one eagle screamed and flapped to the other side of the mew.

“Keep your voice low,” Minerva hissed. “Never, ever yell at a raptor.”

“Sorry.” I stuffed my hands in my pockets and clamped my lips shut.

Minerva lowered herself onto a wooden bench and dropped her head into her hands, massaging her temples again. She didn’t want me working for her—I knew it.

If she fires me, will I have to go to jail?

Above us, the more chilled out eagle lifted a foot and arched it like he was doing bicep curls.

“What … what’s he doing that for?”

“He’s relaxing.” Minerva flexed her ankles in green socks speckled with black bird silhouettes, and the line in her forehead softened.

Kik ik ik! The crazy eagle cackled from a far perch and spread its wings wide.

“Let’s leave them alone now.”

I gripped the bandage around my wrist and stumbled after Minerva down a path and past a redheaded vulture hunched over a tennis ball in its mew. “That’s Xerxes.” She straightened a sign clipped to the wire. “He likes to untie people’s shoelaces.”

Avenging the Owl

Avenging the Owl